· The World According to Woz ·

Wired, Issue 6.09, September 1998

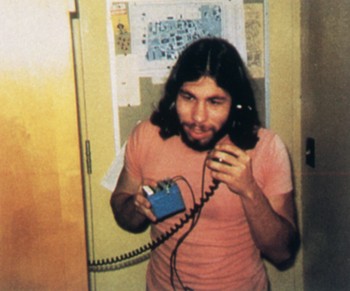

Two decades ago, Stephen Gary Wozniak owned the first dial-a-joke service in the San Francisco Bay area. This was before Wozniak - known among the cognoscenti as Woz - almost woke up the Pope by calling the Vatican on his famed illegal "blue box," before he invented the Apple II and helped launch the personal computer industry, and before he gave up his brilliant engineering career and became a public school teacher.

In 1973, Woz was working for Hewlett-Packard. His dial-a-joke service got more than 2,000 calls a day. He rented answering equipment from the phone company and often used a telephone lineman's handset to take calls live from his tiny kitchen in Cupertino or while lying on the mattress in his bedroom. Extremely shy, Woz didn't have much of a chance to talk to women, but he met his first wife, Alice Robertson, when she called dial-a-joke. Robertson heard a man say, "I bet I can hang up faster than you" - and then he did. Naturally, she called back. A more elegant object-poem on the nature of modern romance is hard to imagine.

There is a recursive logic to the hang-up trick that would be at home in a story by Lewis Carroll. Woz has been systematically experimenting with pranks since he was a child. At Homestead High School in Silicon Valley he printed official-looking cards with false classroom changes on them, allowing him to easily disrupt an entire morning of classes. He built a fake bomb, complete with ominous ticking noises, that caused the evacuation of the school and prompted the guidance counselor to recommend psychiatric treatment.

In college, Woz fabricated a television-interference device that fit into the casing of a magic marker. In the common television room, where sports fans gathered to watch a game, he wielded his device with secretive glee. Pressing the button at crucial moments, Woz could usually tempt one or another of the fans into absurd contortions with the antenna.

Woz, the systems expert, was fascinated not only by how things work, but by the all-too-human and eternally comic assumption that because something appears well organized, it must be trustworthy. In an age when so much of our identity is anchored to strings of digits - cell phones, credit cards, PINs, passwords - the greatest tricksters are the people who play with numbers. Woz's serious work, meanwhile, was characterized by a profound originality that resembled, in its ingenious compression, some of his best pranks. By the time he was 30, he had cofounded Apple and was widely acknowledged as one of the great engineers of his generation.

So why was the Apple II the last computer Woz ever designed?

Today Woz has a regular job teaching computer classes for fifth- through eighth-graders in the Los Gatos, California, school district. Though he does not have a teaching credential and receives no salary, he has worked for the district since 1990. This is his vocation, and he prepares diligently for his classes, working with former students to script the lessons.

A casual and somewhat raucous summer school session is held in Woz's house in the Los Gatos hills. This summer's class of students heading into sixth grade is learning how to uncompress files, send games, and, of course, navigate AOL chat.

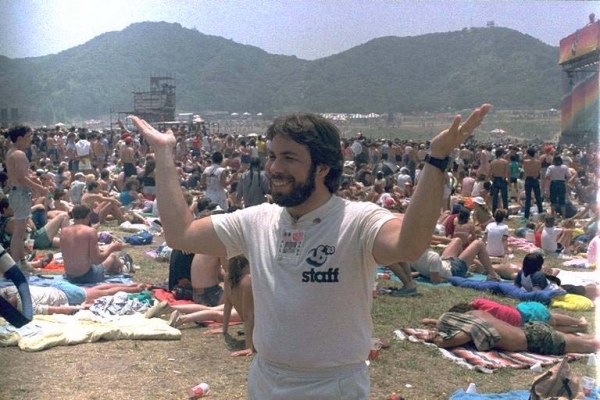

The house is also headquarters for Unuson - short for Unite Us in Song - the company Woz founded and through which he produced two rock festivals during the mid-'80s. Unuson's primary mission today is to support his educational and philanthropic efforts. Woz is not political - he does not consider himself articulate, and the clash of politics bothers him - but he once recommended that as future taxpayers, children should be given the right to vote, an entitlement that would probably lead to better salaries for their teachers. Through Unuson, Woz supports computer training for the local school district by paying for five part-time employees and buying the lab's equipment. He also quietly funds regular election campaigns for special property-tax assessments to support the schools.

Mainly, though, Woz teaches. Eighteen kids in all are enrolled this summer, nine boys and nine girls.

"Steve has yellow teeth!" yells one of the children, as Woz, explaining how to attach pictures and programs to email, displays a large, wide-angled picture of his face onto an overhead screen.

"You can make this picture your whole screen, if you have System 8," Woz says, happily. "Anybody who makes this picture their whole screen could get an A."

The volume decreases a bit as the students pause to reflect.

"You also could get an F," he adds.

The classes are held in an improvised but well-appointed computer lab in Woz's three-car garage. The students' desks, facing two pulldown screens, take up two parking spaces; computer equipment, class supplies, and unopened cases of Jolt occupy the third. Much of the rest of his ranch-style mansion, overlooking the boom without landmarks that is Silicon Valley, is empty. Woz still has an office here, equipped with a user-controllable Internet WozCam that can zoom in on him as he answers email or plays with his dogs, but he lives elsewhere in Los Gatos with his third wife, Suzanne Mulkern. He has been married almost eight years, and he shares custody of his three children from his previous marriage, to Candice Clark: 16-year-old Jesse, 14-year-old Sara, and 10-year-old Gary.

In the overhead demo, Woz moves through the public forums into a private, kid-friendly room.

"Look, somebody wrote 'dildo sucker,'" observes one young lady, her eyes glued to the screen.

Woz's class goes from uproar to attention when he asks. His gifts and popularity as a teacher are obvious. Still, at first glance it is hard to understand how the complexities of AOL chat rooms can hold the interest of the man who helped invent the personal computer.

The UC Berkeley graduating class of 1998 laughs.

"Some laugh, but a few get it," their commencement speaker retorts defensively.

Woz has just finished explaining to the Berkeley graduates that his father taught him an important lesson: "Truth, he said, is more important than anything else. It's much worse to tell a lie than to kill somebody. If you kill somebody and then lie about it, then the lie is worse."

Woz states this assertion with an idiosyncratic certainty that makes no concessions to common sense. Thinking at first that he must be joking, but confused by his straightforward tone, the audience laughs awkwardly and stops suddenly. His statement strikes the class of '98 as obviously false, and those not distracted by visions of champagne bottles chilling in celebratory refrigerators may be wondering how much they really admire this man, who finished his greatest work about the time they entered kindergarten.

Woz is undaunted. In a nonstop, singsong voice, he explains, almost apologetically, the philosophical basis of his success.

"I was lucky," he says. "Keys to happiness came to me that would keep me happy for the whole of my life. It was just accidental. I don't know how many people get it. It's like a religion or something that just popped into my head, walking home from school. One thing was knowing that I was good and believing that I was good and having a good belief about myself. The other was knowing that I could disagree with other people - and, still, I had my own little thought in my head, and it was well structured and it was correct for me. And they could have their own. It's like the song says: 'There ain't no good guy, there ain't no bad guy, there's only you and me and we just disagree.'"

During Woz's childhood, his dad, Jerry Wozniak, was a Lockheed engineer, so he always had somebody to check over what he was doing when he fooled around with electronics. By age 11, Woz had gotten his ham-radio license and his first lesson in hacker moralism: Amateur radio engineers use technology to help humanity, to provide aid in times of disaster, to monitor the airwaves - and, of course, to listen in on uncensored radio traffic.

Woz didn't have many companions during his high school years. He was a true prodigy, whose technical talent quickly outstripped that of his peers and then his teachers. Moreover, computers simply weren't available to students - especially high school students.

"I was all alone," Woz remembers. Once, he told his father that someday he would have a computer of his own. His heart was set on a little 4K Nova. "Well, Steve," said his dad, realistically, "they cost as much as a house." Woz was a little shocked. "Well, I'll live in an apartment," he answered.

During his high school years, Woz designed nearly 50 computers - on paper. He was obsessed. When he did get around to building his own machines, he often had to scrounge for information, get samples of parts from friends who worked at engineering companies, borrow manuals. Spare parts would often be broken; manuals had to be read skeptically.

Woz, like an adolescent butterfly collector or a guy who's really good at drawing pictures of cars, worked at developing his talent without any thought of compensation. "What are the rewards?" he asks. "We didn't have computers back then. You don't get to use it, you don't get a job, you don't get any money. You don't get any acknowledgment. You don't get a title. The rewards are intrinsic. They're in your own mind."

Going to Silicon Valley's Homestead High was a lucky break for a technical prodigy. Not only was the school near the leading engineering companies in the United States, but he also attended high school during the California school system's pre-Proposition 13 glory days, when education spending per student was especially high. (Today, California ranks near the bottom in school spending.)

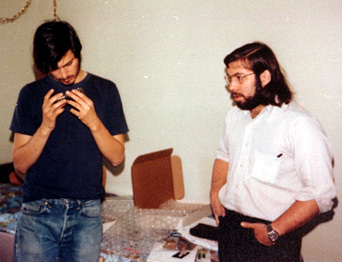

Homestead had a generous and spirited electronics teacher named John McCullom and a well-equipped lab. Four years after Woz left Homestead, the high school graduated another brilliant, technologically oriented student and prankster, Steve Jobs, and through the small network of Silicon Valley computer hobbyists, Woz and Jobs became best friends and inseparable companions.

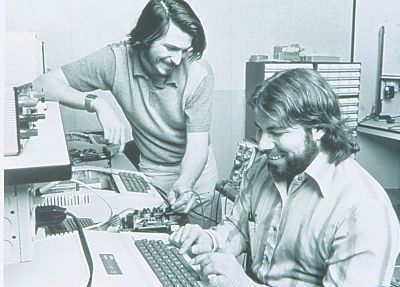

The first Apple - the Apple I - was done for fun, and it was built with what Woz has described as "the oldest, cheapest surplus parts I could find." He knew how to get parts through contacts with friends, but it was Jobs who had the priceless capacity to ask anything of anyone. Woz wanted to make his latest computer as small as possible, and Jobs suggested he use some of the new, 16-pin dynamic RAMs that had recently come out. Woz knew about them but couldn't afford them, and as he later told Byte magazine, he was too shy to call the reps. But Jobs wasn't shy, and he hustled the chips for his friend. Soon Woz had a genuinely tiny computer - about 8 by 11 inches. It ran Basic, and it used only 30 or 40 chips; he knew his fellow hobbyists would be impressed.

The rest of the story has been retold thousands of times. Woz had left college at UC Berkeley to earn money for his fourth year, but he loved working as an engineer at HP and had no interest in leaving his job. He had even offered to design a small computer for HP. But HPturned the offer down. Jobs found money and buyers and persuaded Woz to go into business on the side. The two of them built 200 Apple I computers and sold 175 of them in 10 months.

The owners of an Apple I got a machine with 8K of RAM. After they loaded Woz's 4K Basic into it - by hand, programming in hexadecimal - and added a keyboard and a monitor and wired two transformers onto the power supply, they could use the remaining 4K to run their programs. It was a computer for serious hobbyists, who loved it as they probably have never loved another computer since.

After their success with the Apple I, Jobs saw clearly that Woz's prodigious abilities gave them a chance to create and sell a world-changing microcomputer. Jobs pushed for new features, found more money, and tried to convince Woz to quit his job at HP. Mike Markulla, who came up with the cash, would fund the company only on that condition. "On the ultimatum day I told Mike and Steve that I wouldn't leave HP," recalls Woz. "My love wasn't starting a company and making money, it was designing computers and writing software. Things I could do without a company. I loved HP and wanted the greater job security. Steve went into a frenzy and had my relatives and friends call me and convince me that it was OK to start a company and just be an engineer."

So Woz quit HP, and out of the new corporation came the Apple II. It was smaller, more elegant, and more powerful than anybody thought possible.

The Apple creation myth can either be Woz-centric (great engineering) or Jobs-centric (great product concepts and marketing), but in the early days the two men had such a close, symbiotic relationship that partisan history is meaningless. The world knows Apple for Jobs's machine, the Macintosh, which Woz never worked on, but the company - and perhaps the PC industry itself - owes its existence to his second commercial computer, the Apple II.

Woz looked to Jobs for guidance, and Jobs relied on Woz's engineering genius. One day, while working on the Apple II, Woz mentioned to Jobs that he had noticed something interesting in video addressing. He could make a little change, add two chips, and get hi-res graphics. Was it worth the two extra chips? Jobs said yes.

"At the time," Woz told Byte, "we had no idea that people were going to be able to write games with animation and little characters bouncing all around the screen. It was a neat feature, so we put it in there ... I would take it into Hewlett-Packard to show the engineers. Sometimes they would sit down and say, 'This is the most incredible product I've ever seen in my life.'"

Woz had written the Basic for the Apple II, so he knew how to add commands. He went to work creating a command to plot simple color squares, and then a ball, and then some routines to make the ball bounce around, and, finally - with a few additional resistors and capacitors in the hardware - he had paddles. The Apple II could play games. More important, it could play games programmed in Basic, which every serious hobbyist knew.

Unleashing the power of amateur computer users was the ultimate prank. "Basically, all the game features were put in just so I could show off the game I was familiar with - Breakout - at the Homebrew Computer Club," said Woz. "It seemed like a huge step to me. After designing hardware arcade games, I knew that being able to program them in Basic was going to change the world."

The Apple II was essentially the first and last retail computer designed by a single person. Woz was a programmer and an electrical engineer, and he was able to decide what functions should be designed into the hardware. If he wanted something that would be too cumbersome for the software, he could add hardware. He had the entire design in his head, and he controlled every feature and every compromise.

Woz's brilliance combined with his reserved but uncompromising nature had allowed him to build a computer that was entirely outside the mainstream of computer design. But these same qualities made it difficult for him to stick with Apple as it grew. He wasn't especially interested in running a company or working on a team of closely managed engineers to produce software and hardware upgrades. And the success of Apple rendered a paycheck superfluous. Fading out of the company he'd founded, Woz went back to Berkeley and, despite the fact that he was already rich and famous, completed his undergraduate degree in engineering.

Woz still thought he might be an engineer. His final effort at design and programming came in 1986. He had created a company called CL9 - short for Cloud Nine - to build a universal remote that would control multiple electronic devices. Significantly, to the user, the CL9 device - called Core - did not appear to be a computer. By this time, Woz was beginning to suspect that the computer industry, with its ever shortening, technology-driven cycles of hardware upgrade and software bloat, wasn't going to produce another liberating wave of design anytime soon.

Woz was particularly unhappy with the idea that users wanted computers that were more and more powerful, when he was convinced that most users' needs could be addressed by computers that weren't more powerful - just smaller and cheaper and more thoughtfully designed. Why drive people to bigger and faster computers, taking advantage of their technological insecurity, when basic computing needs were so simple? "People have adequate computing power in the Apple IIe or the Commodore 64," he said at the time.

Woz had the programming for Core partly completed and went to Hawaii to be alone and write the rest of the code. He rented a hotel room and stared out the window for four weeks. He couldn't do it. He couldn't recapture the loneliness and the idealism that had once been the source of his prodigious concentration. He came back and hired other engineers to finish the job.

That same year, Woz gave his first commencement address at Berkeley. His talk, "Humanity Wins!," which he delivered to his own graduating engineering class, argued that technological ingenuity could save the world.

Twelve years later, at the graduate ceremony for the class of '98, there is ample evidence that the dream of technological salvation is enjoying a new peak. Woz's speech is preceded by an award given to the university's most distinguished young scholar, whose life plan, as detailed in the program, includes earning an MD and then a PhD in electrical engineering before starting up his own biotech company to bring his ideas to market.

Engineers are heroes today, but with the faultless anti-timing of the nonconformist, Woz is no longer an engineer.

As employee No. 1, Woz still receives a nominal salary of about $12,000 per year from Apple. But he has never gone back to the computer business or tried to ring the start-up bell again, despite having lost the bulk of his Apple windfall. Of the $150 to $200 million he made after Apple went public, Woz was relieved of nearly half - in a divorce, his commercially unsuccessful rock concerts (the US Festivals lost $25 million in two years), and other ventures. In the late '80s, he put his remaining assets into tax-free municipal bonds, safe from the depredation of wise guys.

WOZ at "US Festival"

Veteran Silicon Valley publisher Stewart Alsop has described Woz as "uniquely undriven," and Woz himself once told an interviewer that "before I was successful designing computers I was successful not having anxieties."

One of the great Woz quotes of all time is his half-apologetic explanation for his failure to be more aggressive about staying rich: "I don't feel attached to my money in normal ways."

Woz's tolerant, ingenuous self-esteem has proved disconcerting to some of those with whom he's done business. The late rock promoter Bill Graham was his partner in the US Festivals. According to Unuson's Jim Valentine, in the wake of that financial disaster, Graham described Woz as "a simpleton." Nonetheless, the two men went on to become partners in the Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View, California, the largest live-music venue between San Francisco and San Jose, in an arrangement that was profitable for Graham, though not for his partner. When Graham planned a peace concert in Moscow before the collapse of the Soviet Union, he went to Woz and came away with a $600,000 donation.

The stories of Woz's financial losses have become part of his legend, making it rather appealing to cast him in the role of the disillusioned innocent in an industry that has tilted more and more toward conventional business - what Woz once thought of as "evil money." People still remember that he was concerned that Apple's stock plan didn't sufficiently reward employees, so he allowed them to purchase shares directly from him before the company went public. Woz even comes with a perfect mythological counterpart, an evil twin, in Steve Jobs. Every greater and lesser Apple chronicler has given some version of this narrative a whirl. In former Apple CEO Gil Amelio's recent book On The Firing Line: My 500 Days at Apple, Amelio wrote that Jobs shamelessly pocketed several hundred dollars owed to Woz from their work on Atari's Breakout game.

Jim Valentine confirms Amelio's story, underlining the obvious fact that Woz's losses reflect badly not on himself, but on certain people "who should have bent over backward not to take advantage of his simplicity and naïveté." But Valentine, who is Woz's close friend and longtime employee, admits that his boss doesn't really share his anger. He has rarely heard Woz make a bitter remark about lost money. Of the fight between Amelio and Jobs over Apple, Woz said simply: "Gil Amelio meets Steve Jobs, game over."

Woz's business activities are slight. Unuson, which employed 30 people during the US Festivals era, is down to about a half-dozen employees (excluding the public school staff he pays), most of whom are part-time. The big house on the hill is now, in Woz's words, "mainly a hangout." It has been the site of some of the Valley's more extravagant all-ages parties, and there is a videogame arcade and a pool with a strange invisible edge over which water endlessly disappears. (He paid millions for the house and is generally acknowledged to have been mercilessly ripped off.)

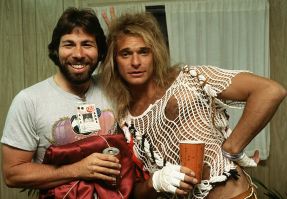

Steve Wozniak kicks it with Van Halen

Woz serves on several boards and briefly attended weekly executive sessions at Apple during Amelio's reign. He argued that the company should focus on kids and teachers - the primary and secondary school market - rather than chase Windows into corporations. This is a direction he has advocated for Apple for more than 10 years, with little impact. Indeed, the three issues about which Woz has been most passionate - focusing on kids, teachers, and schools; giving support to the popular Apple II; and being more open and cooperative with third-party software developers - have all been rejected. He was skeptical of the $400 million purchase of NeXT. He likes to attend concerts at Shoreline, in which he is still a major investor. On a recent evening, he and a friend amused themselves by shining pocket lasers on people in the crowd, and when the jamming got furious they hosted a little laser light show of their own on the canopy above the stage.

For Woz, computer design had been an intense, solitary activity untroubled by complicated social or financial considerations. But nobody designs computers like that anymore. Even the Macintosh team, which created another product nobody thought possible - a computer that nongeeks fell in love with - was too bureaucratic for him. The Macintosh was the product of a chaotic and contentious collaboration, with management, power struggles, and spec sheets, and this was not Woz's style.

He freely admits that he doesn't fit in to the computer industry today. As he sees it, personal computers have reached a plateau. He still explores the new technologies; he stays up to date and experiments and plays. (He is possibly the world's best Tetris player.) But his hope for the future lies with the end of the curve of Moore's Law. Thinking about when designing personal computers might be fun again, Woz projects himself into a time when advances in chip design will have run up against some hard physical limits. Finally, the box will be defined, and, rather than rushing new hardware out the door every six months, we can all take a breather and ask, "How should the software work with the human being?" To him, the current system is driven solely by new generations of hardware that ship too fast, leaving no time for careful study.

Woz and the computer industry have gone their separate ways. As the industry sacrificed creativity to management predictability, he in a sense mortgaged his genius to his life. Woz once said that his success allowed him to come "up from nerdism" and rescued him from the feeling that he was inferior to more socially adept people. He has made his contribution to technology. Now, he's into having friends.

"The way I work requires so much concentration," Woz says. "Getting to know the problem well enough by thinking, thinking, thinking, thinking. And then you try every day to make it a little better, go through it again and again, cutting something off here or there. When I was doing this work well, I didn't have a wife or a girlfriend - I couldn't do anything else."

"Do you miss designing computers?" I ask.

"I miss it," he replies, "but I don't want to do it."

To Woz, the only component of the computing environment that is still lively and interesting is the user. Especially the young user, who might discover some possibility not yet known in the relatively hidebound space that most of us unquestioningly accept. Maybe some kid will look at the problem with a fresh mind. And maybe Woz, in the classroom, will be part of it.

Woz gave a second commencement speech this year. At Berkeley, he spoke to the beneficiaries of the best public education in the state. The second talk was to the graduates of Southwestern Oregon Community College, a two-year school that serves 13,000 students - most of whom work and go to school part-time - in the coastal city of Coos Bay.

The commencement ceremony is held in the basketball auditorium of the local high school. Around the rafters hang banners emblazoned with the timber-related mascots - the Springfield Millers, the South Eugene Axemen - of the region's high schools.

For about $40 per credit, students at Southwestern Oregon Community College can begin to attempt to connect themselves to the machines that Woz helped invent. Technical training is in high demand, and more and more classroom material is presented via computer. Mike Gaudette, the school's press liaison and grant writer, told me that a funder recently asked him whether he could prove that computers enhance education. Gaudette's honest answer was that the question was beside the point. "If students read history," he said, "then when they finish their course they are better at reading. When they work and study history on a computer, do they know history better? No. But they know how to use a computer." This outcome, Gaudette pointed out, is now a primary goal.

Touring the college's labs, with their rows of personal computers, I find it difficult to connect this form of computer education with the idealism and excitement of the Homebrew Computer Club, or with Woz. The beige rows of keyboards and monitors look just like something out of yesterday's typing workshops, where students without access to venture capital were trained to serve the machines commonly used in business.

Undaunted, Woz describes for this graduating class his original vision of a technological revolution. Although he no longer designs computers, he retains something of the distracted and childlike qualities of the übernerd, and his delivery is fast, disjointed, and extremely personal. "All of a sudden," Woz says, remembering his days at Hewlett-Packard, "affordable computers were coming! Computers that people could own! We could have them in our homes. There would be a revolution, and they'd be in every home. And we spoke in clubs, and we had a big club, and it grew to 500 members and it was huge and we just hung on every word. And the big computer companies, the ones that already existed, said, 'It's a little passing fad like ham radio. It will go away. It just doesn't matter. Nobody is going to want a computer in their home.'

"Well, that's right. The computers were ugly and they were big monstrosities and they didn't look like anything you'd want in the home. They looked like some big commercial piece of equipment with switches and things that you'd have to have a technician working in your house to keep it maintained. Our idea was that these computers were going to free us and allow us to organize. They were going to empower us. We could sit down and write programs that did more than our company's programs on their big million-dollar computers did. And little fifth-graders would go into companies and write a better program than the top gurus being paid the top salary, and it was going to turn the tables over. We were excited by this revolutionary talk.

"The club was all about giving, because back then there were no dollars in this business. It was: Give some knowledge. Write down a program you've got. Write down how to build a certain device. Offer some help. Offer some information. Offer some parts at a good price. Offer your own time."

Revolutionary excitement is always sparked when powerful information is suddenly shared. But, he goes on, this is not the mood of the computer industry today.

"Now computers are a big business," Woz challenges from the podium. "Sometimes I wonder, 'Am I the master of the computer?' When we talked in our club, computers were going to be so simple to use that everyone was going to be a master and be able to create whatever they wanted to. Now I feel like a slave sometimes. I have to do it their way. It wasn't the feeling we were after in the first days."

Southwestern Oregon Community College offers a new two-year degree in manufacturing technology. For many of Woz's listeners, education means an efficient occupational introduction to the jobs that have replaced fishing and mill work and for which they will have to move to the new, far-flung suburbs of Seattle or Silicon Valley. The reality here is that the personal computer, once imagined as a source of creative joy, has become a routine piece of office equipment.

It is an environment that begs for disruption. If the college's regimented computer lab is to be redeemed, it will be through the creativity of the teachers who stand in front and exploit those spaces in the system where creativity remains possible.

A few days after his commencement address, Woz is back in Los Gatos taking his students through lessons in instant messaging and Buddy Lists and email. The day isn't complete until one of the boys, taking advantage of the constant commotion, sneaks onto his friend's AOL account and sends an insincere message of affection to a girl sitting nearby. By the end of the class, the garage doors are half open and parents are coming and going for their kids.

"I've been out fueling the economy," one dad, wearing shorts and Tevas, announces as he arrives for his daughter. "I've bought you a bicycle," he tells her.

But the girls are more interested in their email.

"Don't tell him what it says," says one, rather obviously.

"Sorry, I can't tell you," her friend obliges.

Woz, kicking back in his chair with his little white dog Sophie asleep on his lap, is thrilled.

"Now don't embarrass anybody," he says calmly. "Just tell us what it said!"

"I can't tell you," the email recipient says, "but I can show you." (She proceeds to make the American Sign Language gesture for "I love you.")

Electronic pranks engender a secret revolutionary order of tricksters for which the girls, with their sign language, are auditioning. Woz loves it. It is not the simple commands on AOL that interest him, but the flash of recognition that a system, no matter how complicated, is still only a system; that it can be explored, understood, and altered.

A long time ago, Woz had a number that matched the Pan Am reservation number. People in Silicon Valley's 408 area code who failed to dial 800 would get him instead - one of those minor miracles arranged by Charles Dickens, or by God. You think you've got Pan Am - but instead you've got Woz, who explored many variants of the special, rare case of the prank phone call initiated by the recipient. In one prank, which has the cruel simplicity of a Zen koan, he would quickly tell the caller that as the millionth passenger on Pan Am, they had won a lifetime of free travel. In the middle of collecting the caller's personal information, he would hang up, leaving them to confusedly call back and attempt to get confirmation of their fabulous and elusive prize.

The proof that people are not completely slaves to our machines is that when the system fails, its failures are not necessarily random.

The phone system, with its complexity, vulnerability, and illusion of privacy, is the natural home of the technological trickster. In Shakespeare, the prankster's domain is an enchanted forest.Today, it is the mysterious convolutions of the communications network.

Among his other activities, Woz collects phone numbers, and his longtime goal has been to acquire a number with seven matching digits. But for most of Woz's life there were no Silicon Valley exchanges with three matching digits, so Woz had to be satisfied with numbers like 221-1111.

Then, one day, while eavesdropping on cell phone calls, Woz begin hearing a new exchange: 888. And then, after more months of scheming and waiting, he had it: 888-8888. This was his new cell-phone number, and his greatest philonumerical triumph.

The number proved unusable. It received more than a hundred wrong numbers a day. Given that the number is virtually impossible to misdial, this traffic was baffling. More strange still, there was never anybody talking on the other end of the line. Just silence. Or, not silence really, but dead air, sometimes with the sound of a television in the background, or somebody talking softly in English or Spanish, or bizarre gurgling noises. Woz listened intently.

Then, one day, with the phone pressed to his ear, Woz heard a woman say, at a distance, "Hey, what are you doing with that?" The receiver was snatched up and slammed down.

Suddenly, it all made sense: the hundreds of calls, the dead air, the gurgling sounds. Babies. They were picking up the receiver and pressing a button at the bottom of the handset. Again and again. It made a noise: "Beep beep beep beep beep beep beep."

The children of America were making their first prank call.

And the person who answered the phone was Woz.

Wired, Issue 6.09, September 1998

|

![]()