What the other Steve has to say...

Date: xx. xx. 2005

Author: David Pescovitz

Published at: www.coe.berkeley.edu

With friendly permission by Patti at berkeley.edu

· · · David Pescovitz ·The Wizard Who’s Woz · · ·

A Conversation with Steve Wozniak

Buck’s of Woodside is an unassuming diner in the Silicon Valley known for its kitschy decor and first-rate flapjacks. For computer industry insiders, it's also legendary as schmooze central for the Valley’s venture capital community. Buck’s is the place where Netscape was hatched, PayPal got funded, and countless other dot-coms were seeded. Thirty years ago in a Los Altos garage not far from Buck’s, Steve Wozniak, now a Silicon Valley icon, and Steve Jobs, who today is CEO of Apple and Pixar, were burning the midnight solder, building the Apple I.

|

Steve Wozniak is still a talented tinkerer. He recently built a key programmer for the Segway, an electric scooter invented by Dean Kamen, that stores speeds in a key. Wozniak routinely transports two or three of the $5,000 scooters in the back of his car for teammates to use at his weekly Segway Polo match.

BART NAGEL PHOTO |

Woz, as his friends call him, was born

in 1950, the son of a Lockheed engineer. Growing up in San Jose, California, he was a talented tinkerer, earning his Ham Radio license in sixth grade and designing his first computer at age 13. It played Tic-Tac-Toe.

He spent his college years at the University of Colorado, De Anza College, and finally, Berkeley’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences. To afford his electronics habit on a student budget, Wozniak and his friend Steve Jobs sold “blue boxes,” illegal devices that enabled anyone to make free long–distance calls. In 1976, Woz dropped out of Berkeley to return to the South Bay, landing a job designing calculator chips for Hewlett-Packard. On the side he wrote arcade game software for Atari, where Jobs worked.

In his off hours, Wozniak hung out with the Homebrew Computer Club, a legendary geek gathering founded in 1975 by hacker hobbyists in Palo Alto. They mainly exchanged tips and tricks for the first personal computer kit, the Altair 8000. Woz and Jobs couldn’t afford an Altair, so in 1976 they built their own personal computer. Because Jobs once worked in an orchard, they dubbed their machine the Apple I. It made a big splash at the Homebrew Computer Club, and Jobs was able to score a bonanza $50,000 order from a Mountain View computer store called The Byte Shop. Wozniak's father kindly removed his car restoration tools from the family garage and production began on the Apple I. The next year, Woz introduced the faster Apple II, complete with color graphics, and quit his job at HP. Then in 1980, Apple Computer hit Wall Street, garnering the largest IPO since Ford Motor Company went public.

After recovering from a private plane crash in 1981, Wozniak took a hiatus from Apple. During that time, he orchestrated the US Festivals, celebrations of rock music, culture, and technology. By 1985, he and Apple had parted ways entirely, and Woz returned to Berkeley to finish his senior undergraduate year, graduating in May 1986.

He spent much of the 1980s and 1990s as a full-time philanthropist, aiding the renewal of downtown San Jose through donations to the city’s ballet and Children’s Discovery Museum, even teaching in the school district of Los Gatos where he currently lives. These days, his mind is incubating another new digital technology that could, yet again, cut a swath of change in our daily lives.

Q: Legend has it that the name on your 1986 Berkeley diploma is not Steve Wozniak.

Woz: I asked that the name on the diploma be Rocky Raccoon Clark. Clark was my wife’s maiden name and she went to Berkeley. When I went back to finish my degree, Apple was already well known. I was going to take computer classes and get A-minuses and B-pluses and I didn’t want people thinking, “Why didn’t Woz get all A-pluses?”

Q: You're quite the prankster.

Woz: After my initial year at Berkeley I started the first dial-a-joke in the Bay Area. Back then you couldn’t really get an answering machine unless you were a movie theater. Even then, you’d have to lease it from the phone company. So that’s what I did. I met my first wife when she called the dial-a-joke line. Usually I’d just turn the machine on, but I happened to answer that time. I said, “I bet I can hang up faster than you,” and hung up. But she called back and we talked. I’ve always been extremely involved in pranking. Some of my pranks are so complicated that they take days, even months, to work out. I think humor is a creative act. Pranks are just a creative form of logic. My iPod is filled with comedy as well as songs.

Q: In 1982 and 1983, you orchestrated the US Festivals. Do you still go to live music concerts?

Woz: Absolutely. I was one of the founders of the Shoreline Amphitheatre with Bill Graham and I have been to almost every concert since it opened in 1986.

President George H.W. Bush presented Wozniak with the prestigious National Science and Technology Medal in 1993.

PHOTO COURTESY DAN SOKOL |

Q: I know that philanthropy is also a big part of your life. What drove you to give away so much of your personal wealth?

Woz: I had always envisioned a life with a reasonable engineer’s income, a lifestyle similar to that in which I grew up. I had never developed lofty goals of wealth or possessions. I didn’t think that I’d have enough money to take a vacation in Hawaii or to even own a home. I had grown up shy and didn't have a social group but I fit in with the people interested in computers. I listened, I talked a bit, I designed stuff, and I showed it off. This was for social reasons, not money. I wanted to share my knowledge and educate others about computers and point out some clever design techniques of my own. So when we did achieve some major success, I had a lot of wealth that I had not pursued.

Q: Initially, your charity was in the form of the technology you invented.

Woz: Because I was associated with computers, I responded to requests for donations by sending a lot of computers to people. Sometimes it was to a school that was strapped for resources but that really wanted this new technology. Sometimes it was a person who was in the ruts and I thought a computer might bring them out of it. I also had a desire to always be good to my schools, so I contributed a lot that way.

Q: In the 1990s, you became even more involved in schools by actually teaching on a regular basis.

Woz: I taught computers for eight years—young kids, elementary school, middle school, high school, and even teachers. I taught up to seven days a week. I wrote all my own material. I enjoyed it very much. I basically sponsored the full cost of everything, but it was so much fun and really worthwhile.

Q: In many ways, you’re a role model to hackers everywhere. And of course, I mean “hacker" in the original sense, as someone who pushes the capabilities of a technology. Do you miss wielding the soldering iron?

Woz: I do. A couple of years ago, I built a Segway [electric scooter used in pedestrian areas, invented by Dean Kamen] key programmer. The speeds you can go are stored in a key, so I made the device so I could program in my own speed. It’s just one microprocessor that’s basically equivalent to the processor in the Apple II. I still enjoy doing that kind of thing more than anything in the world.

Q: That do-it-yourself computer hacker mindset seemed to have faded a bit during the 1980s and 1990s, but it seems to be reemerging.

Woz: Before 1975 or 1976, it took huge teams to build computers. Then, there was a short period where one person could design and build things like the Apple. After that though, what you could accomplish was dwarfed by whatever the big companies did with their dollars. When we were growing up, we built little electronic parts and systems like house-to-house intercoms. Then we could tell the other kids at school about it and we stood out as a little special. If you’re shy, that kind of thing gives you something to talk about.

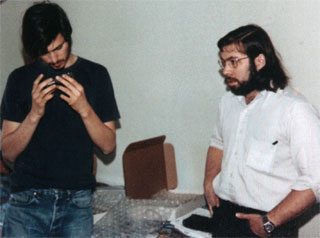

Two young wizards, Steve Wozniak (right) and Steve Jobs, test their home-built Apple I at Jobs’s house in 1975.

MARGARET WOZNIAK PHOTO |

Q: When you and Steve Jobs were creating the first Apple, did you have any idea that you would be helping launch a revolution?

Woz: We did talk “big” talk of revolutionizing the world. I never thought that so many people would consider us the source of this change. It was due to technology advances, and various people were going to approach it in many ways. We were just one of those many pursuing the future of computers in every home. The revolution very quickly surpassed what I ever imagined.

Q: Are you pleased with the evolution of the personal computer?

Woz: When we started, the focus was on doing as much as possible with as little as possible, in terms of resources. Our first products, the Apple I and Apple II, were tools that you could learn to use and write programs to solve your challenges to become more of a master in your life and work. But as the revenues of this new market grew, lots of other people wrote the programs for you. So our users learned to use those programs rather than write their own. Many advances in computers, the GUI [graphical user interfaces] first implemented well by Apple with the Macintosh, were so much more important in giving us the things we appreciate about a computer today.

Q: In light of the Internet, the proliferation of wireless mobile devices, and the pervasive computing that Wheels of Zeus [a company founded in 2001 to engineer breakthrough location technologies] is helping introduce, how do you envision the computer landscape of 2020?

Woz: When we were in Apple, I could accurately predict what would happen a year out because we were working on it. But if I tried to predict two years out I was usually wrong—unexpected things would appear and there would be a better way of doing things.

As we move forward, we are developing standards where things work reliably, as expected. But we are also introducing newer better modes of communication, both wired and wireless. We have so many types of media and modes of computer communication today that it often means that when you are pushing the state of the art and pushing the future, things don’t always work well together. We can demonstrate things working in ways that simplify our lives, but change one parameter or device and it’s a frustrating effort to get things working. I don’t see that changing, ever.

Will the number of media types and communication methods settle down to a few accepted ones by 2020? In my opinion, like the end of Moore’s law, someday this is likely. Remember that we grew up with about four types of media—33 RPM, 78 RPM, 35-mm film, and 120-mm film. And they always worked. Since then we’ve had a real proliferation: CDs, laserdisks, a host of magneto-optical media, floppies and HDs of various sizes, flash RAMs, SmartMedia, Compact Flash, Memory Sticks, and on and on; not to mention various tape media. There’s no end and no single standard that people use.

The best thing for 2020 would be if all this settles out, but that would almost require us to not have many extremely good things to create. See the problem? You can’t even hope for it, really, and you certainly can’t predict it.

Q: Apple has an amazingly dedicated and vocal community of users. Some even refer to the “Cult of Macintosh,” and they’re only half-joking. Beyond the technology, what is it about Apple that fuels such passion?

Woz: The main reason is that Steve and I started from nothing but had good motivations about how we could change the world positively. That still comes out today. Some people are so endeared to it that it’s almost as gripping as a religion. I honestly believe that it’s about “thinking differently.” People who don’t want to go along with the masses have a place in the world with Apple. |

![]()